Secret Stories Behind The Greatest Classical Compositions: Mozart's Requiem

The beautiful and haunting Requiem Mass in D minor (K.626) is one of Mozart’s great musical works – and his last. Not only is it a masterpiece, but it carries with it much speculation and myth, making it a music history mystery!

According to musicologists and historians, the story goes like this: In the summer of 1791 a mysterious messenger appeared at Mozart’s home representing an unnamed party who wanted to commission Mozart to write a requiem, with the understanding that he would never know the identity of the patron.

By the time Mozart completed the Magic Flute in September of that same year, his health was not good, but he was intrigued, and a little spooked, by the request for the Requiem and obsessively started to work on it. As his condition continued to deteriorate, he believed he had been cursed to write a requiem for himself, convinced he was about to die.

Mozart only completed the orchestral and vocal parts of two movements for the Requiem –"Requiem aeternam" and "Kyrie"– when he died on December 5, 1791. Other movements were drafted in skeleton form and left with notes for completion, which included accompaniment, inner harmonies, and orchestra doubling to the vocal parts.

Completing the incomplete

Mozart’s wife Constanze was fraught with fear that if the work were not completed the patron would not pay the balance of money owed for the commission. She asked Joseph Eybler to complete the work, but after a mere orchestration to one section, he passed it over to Mozart’s student, Franz Xaver Süssmayer, whom Mozart had given the detailed instruction to for completion.

Süssmayr borrowed some of Eybler's work and added his own orchestration to the movements from the “Kyrie” and the “Lacrymosa” as well as adding several new movements which would normally comprise a Requiem: Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei. He then added a final section, “Lux aeterna” by adapting the opening two movements which Mozart had written, to the different words which finish the Requiem mass.

According to both Süssmayr and Constanze, this was done according to Mozart's directions. Some historians feel that Mozart would never have repeated the opening two sections if he had survived to finish the work. It is speculated that Süssmayr may have had the help of other composers. When finished, Süssmayer copied the entire score in his own handwriting (making it almost impossible to determine who wrote which parts), forged Mozart’s signature at the bottom with the date of 1792, and gave it to the enigmatic patron.

It turns out that the mysterious sponsor was not Mozart’s arch-rival Antonio Salieri, as depicted in the Oscar-winning film Amadeus. It was Count Franz von Walsegg-Stuppach, who hoped to pass off Mozart’s Requiem as his own composition to commemorate his late wife. It would be ten years before Constanze was able to persuade Walsegg to acknowledge Mozart as the Requiem’s true composer.

The various complete and incomplete manuscripts of the Requiem eventually turned up in the 19th century, with many of the figures involved leaving ambiguous statements on record as to how they were involved in completing the work. Despite controversy over how much of the Requiem is authentic Mozart, the commonly performed Süssmayr version has become widely accepted, even though alternative completions provide logical and compelling solutions for the work.

The Requiem is comprised of the following eight movements in Süssmayr’s Completed manuscript:

- Introitus (Requiem asternam)

- Kyrie

- Sequentia (Dies irae, Tuba Mirum, Rex Tremendae, Recordare, Confutatis, Lacrimosa)

- Offertorium (Domine Jesu Hostias)

- Sanctus

- Benedictus

- Agnus Dei

- Communio (Lux aeterna, Cum sanctis tuis)

The Stolen Autograph

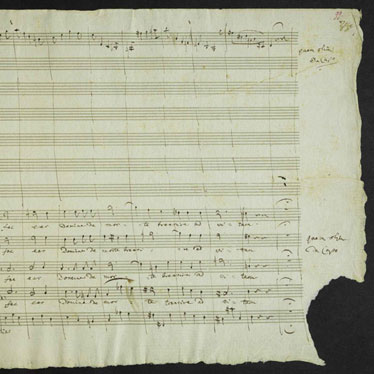

Mozart’s autographed manuscript of notes for the Requiem was displayed at the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels. Somehow, someone gained access to the manuscript and tore off the bottom right-hand corner of the last page (folio 99r/45r), containing the words "Quam olim d: C:" (an instruction that the "Quam olim" fugue of the Domine Jesu was to be repeated da capo, at the end of the Hostias). The vandal was never caught, and the fragment never recovered (see image above). If the most common authorship theory is true, then "Quam olim d: C:" might very well have been the last words Mozart wrote before he died.

So, we have one of the world's greatest composer, who died writing what turned out to be his own Requiem. Despite the mystery of who may have written what, Beethoven said it best, “If Mozart did not write the music, then the man who wrote it was a Mozart.” Some musicologists feel the real mystery of the piece is not so much the story you have read here, but the music that Mozart did manage to write – Breathtaking and otherworldly. Take a listen for yourself. Here’s a link to a recording of the original Mozart autographed manuscript.

Below is Herbert von Karajan conducting the traditional Süssmayr version. Tell us what you think.

Top image: Last page of Mozart’s Arbeitspartitur of Requiem (K626), 1791. Written in the right margin: "quam olim da capo," was vandalized in 1958. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, Austria. Public Domain. Courtesy of Wiki Commons.